What do you want to be when you grow up?

I thought I wanted to be an electrical engineer. I enjoyed it in high school, and I was good at it, so it made sense to choose an engineering degree. Reality became more apparent to me when I got to university and discovered that I genuinely despised one of the fundamental subjects. It probably should have been a deal breaker but by that point, I was already more than halfway through and felt I was in too deep to start all over.

So, what in the world was I going to do with my engineering degree?

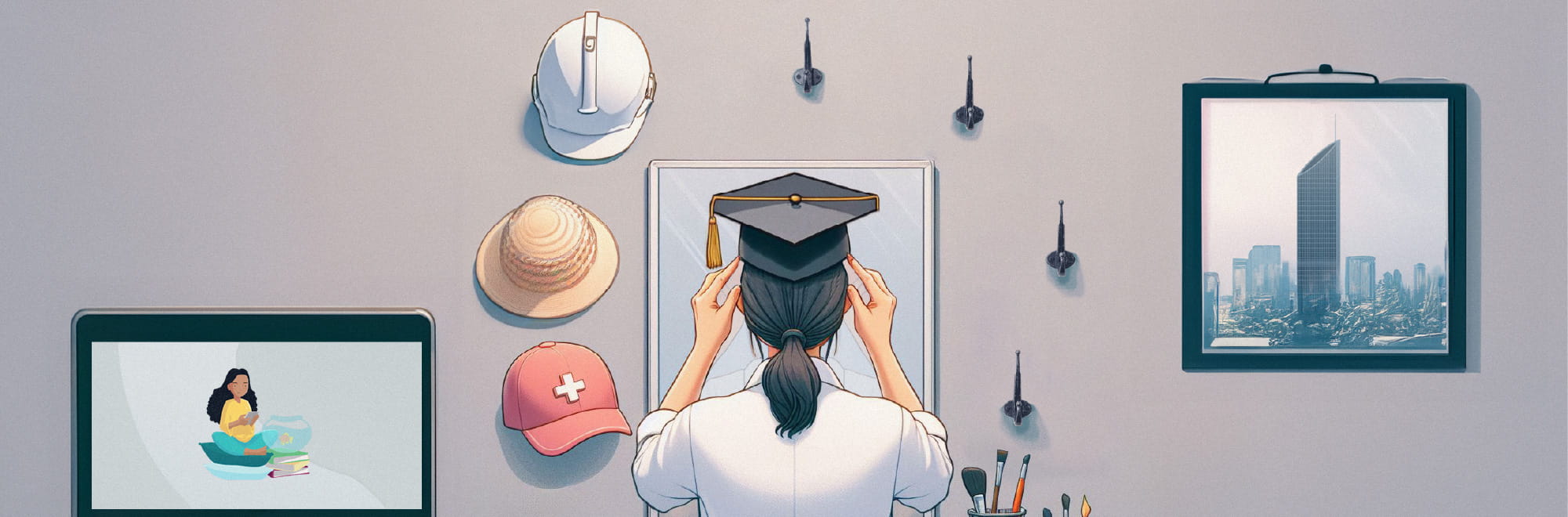

There seems to be an unwritten rule that we must adhere to a predetermined career trajectory, starting from your first book and play set, all the way to the gown and tassel. And graduating is just the beginning. Like mass-produced factory cookies, we graduates get turned out in unprecedented numbers, our path on the conveyor belt neatly mapped out. Until one cookie demands sprinkles – or in my case, to be an entirely different cookie.

When I interviewed for an electrical engineer position, I was completely honest about my interests and career aspirations, which naturally made the interviewer ask: "is this really what you want?" In other situations, my answer would have raised eyebrows and have cost me any chance of being offered a job, so imagine my surprise when a few days later I received a call asking if I wanted to apply for another role instead. That was my entry into project management, which I didn't yet know would become my first career.

Could our tertiary degrees (or our expectations from it) be holding us back from unlocking our fullest potential? Are our beliefs about the link between success and a multi-year degree just a lie? And more importantly, how would the future of our workforce change if organisations could see people before degrees?

Degree inflation

A four-year degree has become the de facto requirement for many companies to even consider your résumé, irrespective of whether the position warrants one or not. Although more education for more people is a good thing, this phenomenon of degree inflation is hurting industries and individuals alike. Not only does it provide lesser opportunities for people without degrees, it also makes it harder for employers to meet the rising demand for talent.

But does this mean that tertiary degrees should die? Of course not, there are many professions that require certain skills and training that can only be attained in university, just consider the likes of medicine, law, and yes, even engineering – but it's a little more complicated than that.

There are several things to unpack here starting with: how important is having a four-year degree, really, in each role or position? And if a person does have a degree, how diverse are the opportunities that can be offered to them? Most importantly, what if young professionals like me don't know yet what we want? What should we do?

A recent study found 60 per cent of young professionals feel overwhelmed or unable to cope due to the pressure to succeed in their careers, which stems from our own expectations and the desire to conform to the years spent pursuing a degree. We don't want to feel we've wasted all that time and money.

During an era of so much uncertainty, can we ask organisations to extend the 'flexibility benefit' not only in our work set-ups but also in how we apply our degrees and experiences? Will they take a chance on us?

More than one way to skin a cat

We often hold ourselves to the expectation that if we lack official documentation validating a particular skill, we are deemed inadequate for certain job applications. The reality is, the skills acquired during university learning, and the experiences from the 'school of life', can be applied to many jobs – not just the most obvious or expected.

Take law school graduate Amena Kheshtchin-Kamel as an example, who studied law because her parents wanted her to become either an engineer, lawyer, or doctor – even though her passion is in storytelling. She decided to make her law degree work in her favour and used the seemingly odd combination of screen-writing and practising law to make herself stand out in Hollywood as a writer/producer.

Big companies like Google started opening their doors for new workforce entrants with untraditional backgrounds, recognising the fact that formal education is just one piece of the puzzle. Between 2011 and 2021, IBM's job postings that required a four-year degree fell from 95 per cent to under 50 per cent. Experts increasingly agree that such an approach widens the talent pool, allows for more unique and nuanced skills and viewpoints, and levels the playing field for more people – including women who are under-represented in fields like technology, engineering and construction.

Skills are the ultimate deciding factor, irrespective of where and how those skills were obtained. Getting a degree, or getting the "right" degree, is not the be-all and end-all in finding the right person for the role or landing that perfect job. As young professionals, we need to shift our mindset towards recognising the inherent value of our skillset, and leverage our life experiences to make them relevant to allow more opportunities for growth.

Discover why collaboration, confidence, and human insight remain essential in engineering’s AI era.

Listen to the PodcastA constant state of 'figuring things out'

This shift in mindset – both for employers and its people – has never been more important, especially with the unpredictability brought by the pandemic. According to a recent survey among teens in Auckland, 52.9 per cent of students had a clear career path in mind before COVID-19 but 41.7 per cent either pivoted or had a complete change of heart after.

This, however, has been a long time coming even before the pandemic. An Emsi report agrees that the college-to-career path is typically not linear, but more of a swirl. There really isn't such a thing as neat cohorts entering high-profile careers with perfect intentions like an army of tin soldiers. Rather, you see real people moving and finding their way in the market and adapting as they go.

Whilst I'm still in the early stages of my career, I find this to be true. I was fixated on becoming an electrical engineer but I didn't become one. Will I stick with the project management path moving forward? Maybe. Maybe not.

The beauty of accepting that you will always be in a state of figuring things out is being open to taking advantage of all the opportunities that cross your path and having the freedom to reinvent yourself without feeling your identity is tied to a degree title. And for businesses, the power is in unlocking and unleashing the truest potential of their people and mutually benefitting from what may have been considered impossible. Who knows? We might just find nothing short of magnificent and remarkable.

Applications for Aurecon's Graduate Programme in Australia and New Zealand are now open until 7 April 2024. Apply now!