How did you get to where you are today? Undoubtedly, there have been many factors that contributed to your journey so far – some that may have been in your control and some that haven't. The big question is: how aware are you of them?

Have you completed a university degree? Did you attend a private high school? Did you have access to books and computers at home while growing up? Do your parents work in an office? Did you have any work connections before entering the workforce?

These questions are just a few examples that point to the privileges and disadvantages we've gained or inherited due to our social class. It's not always a comfortable conversation, and in fact can be quite the opposite. Often, it's a conversation that's not even had.

Contrasting emotions of guilt or shame over our backgrounds makes this a challenging subject to broach. In fact, often those with social privilege don't even recognise the advantages they had that helped them reach their goals, which is what makes it so difficult to bring to collective consciousness and then address.

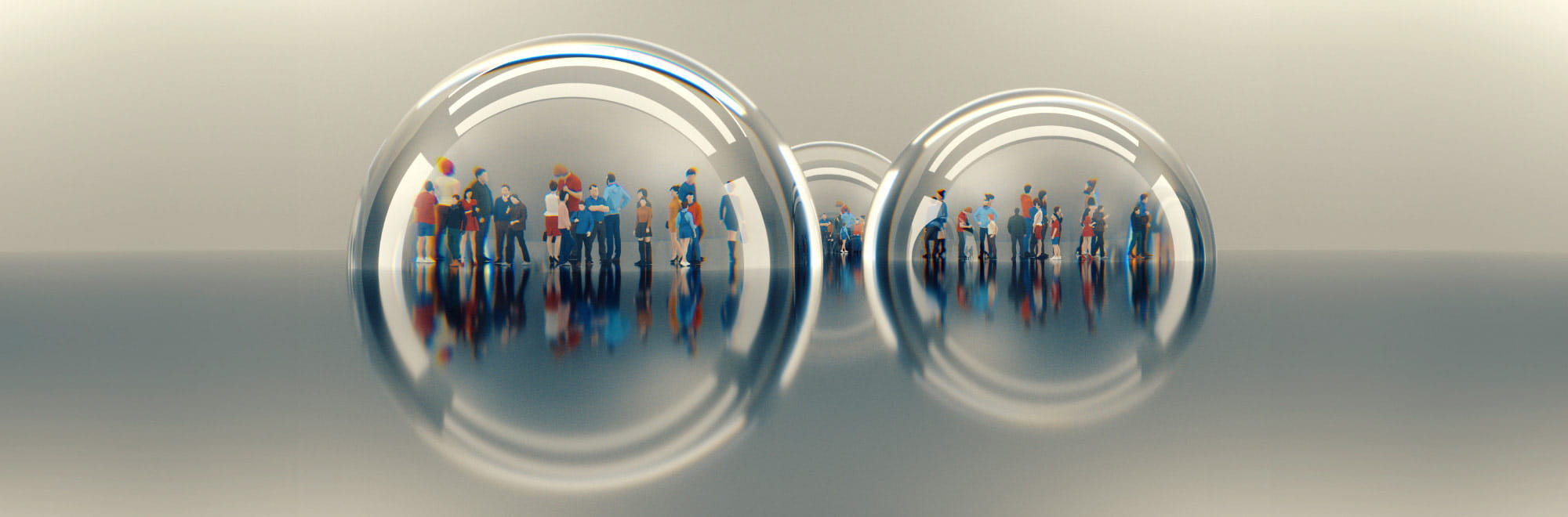

While reasonable progress has been made to achieve diversity, equity and inclusion, based on factors such as gender, cultural background and sexual orientation... Social class remains an invisible barrier to career success.

Our social backgrounds shape who we are, how we see the world and in some cases, how we are identified by others and how we self-identify, or even label, and therefore limit or stretch ourselves.

More importantly, it has the potential to influence access to jobs, hiring decisions, promotions and advancement; and whether an individual is perceived to be competent, ambitious, and committed. For example, if our parents went to university, we're more likely to think we too should go to university. If our parents didn't, it might not even occur to us that it's an option, and yet, a university degree is often seen as an enabler to start a successful career.

In 2020, Diversity Council Australia's (DCA) research found that of all other diversity demographics investigated in DCA-Suncorps Inclusion@Work Index, class is the most strongly linked to workers' experience of inclusion and one of the most strongly linked to exclusion.

So, how do we see it if it's invisible?

Access ain't inclusion

In the realm of academia, where securing a place within a prestigious institution or gaining access to gainful employment already presents significant challenges, eminent sociologist Dr. Anthony Abraham Jack said that is only half the battle.

Jack undertook research exploring the overlooked diversity among lower-income undergraduates. He observed how colleges in America, similar to many organisations, have invested millions in diversity recruitment, but have thought less about what to do once students arrive on campus. He plainly sums it up by saying, "access ain't inclusion."

When a student enters university, or a new recruit enters the workplace, they will undoubtedly encounter hidden curricula or codes of unwritten rules and expectations. It will likely be assumed they bring with them similar backgrounds and experiences and that, as such, everyone is equally equipped to succeed. They're not.

Both at university and in the workplace, many socially disadvantaged individuals, especially those with low cultural capital (more on this later), struggle to navigate their new environment of informal conventions and to effectively leverage opportunities. Does this mean they are less skilled or not as smart as others? Definitely not. But how can we level the playing field? Is that even at all possible?

Building cultural capital

Social class often signals an individual's cultural capital, which refers to an individual's non-financial assets like their knowledge, skills, social networks, and cultural experiences (including skills such as using chopsticks or life experiences such as travel). This is often seen as a key indicator of success because it influences ‒ even more so than money ‒ academic readiness, communication skills, cultural awareness, access to networks, confidence, and adaptability.

While social class encompasses economic aspects, cultural capital focuses on the cultural and educational elements that contribute to a person's social standing.

Organisations wanting to bridge the cultural capital gap for their employees could start by understanding that hiring for "culture fit" can result in unconsciously favouring certain backgrounds and discriminating against others.

If irrelevant class-based criteria are referenced when making hiring or promotion decisions, workers with lower socio-economic status may disengage and feel unwilling or unable to be their authentic selves. They may have the tendency to mask all visible, behavioural, and attitudinal indicators in an attempt to fit in with their 'classier' colleagues.

Accordingly, instead of assessing people for culture fit, what if we think of ways to foster and project a truly inclusive culture that would encourage them to apply in the first instance and then help them reach their full potential?

After all, the most important aspects of an organisation's culture aren't defined by what school we graduated in or where we live. What matters most to employees is that they feel respected and valued in the workplace.

Social class is certainly a bigger issue that goes beyond classrooms and office walls, but considering we spend the majority of our days in school and then later in the office, aren't these the best places to start?

While we can't alter the inherent privileges and disadvantages stemming from our origins, we each have an opportunity to enact change within the employment settings we operate in to foster a fairer and more prosperous workplace, no matter where you sit on the scale of advantage.

By recognising and dismantling the hidden barriers that sustain disparities and by humanising the issue, we can help make them visible to ensure individuals are not confined by their circumstances and can contribute to the collective welfare of an organisation.

Once we see the disadvantages and advantages of social class, it becomes a catalyst for heightened awareness, prompting us to question what else we have taken for granted or what unfair expectations or exclusions we may have placed on ourselves and others.