The concept of ‘leapfrogging’ – or the idea that by embracing modern systems, poorly developed areas can develop rapidly without the need to go through intermediary steps – has captured imaginations. With leapfrogging, new ways of thinking rapidly lead to new ways of doing and being – and new ways of competing.

We know that we can apply new technology to less developed regions with great success. But what of the opposite? If innovation trickles down, can it also trickle up? While developing countries may be prime candidates for leapfrogging technologies they are also rich potential sources for reverse innovation.

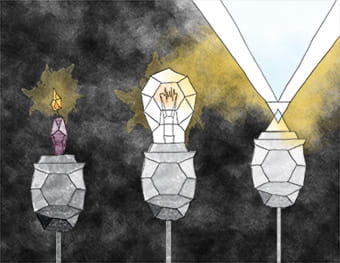

The massive successes of mobile networks in Africa transformed one of the world’s least connected places into the epicentre of a communications earthquake. This ‘leapfrog’ overcame problems such as “no line infrastructure!”, “limited electricity networks!”, and “a population mostly without bank accounts!” How? Quite quickly, beyond all original forecasts, with cheap handsets, mobile base stations and unique prepayment packages.

When we think about leapfrogging, we often think about superimposing a cutting-edge technology on a market that is underdeveloped. Leapfrogging leads to solutions that can allow you to completely overtake your competition, despite the fact that they are better established, with bigger infrastructure and more resources. But does leapfrogging only work in one direction?

Leap in reverse

In Africa adversity is a powerful driver of innovation. When you absolutely have to; when you have no other option; when your back is up against the wall – then true innovation comes to the fore. This is often referred to as ‘survival’ in developing nations, but is there a lesson in this for developed nations?

Will alternative energy solutions, specifically on the African continent, become a major disruptor?

Will alternative energy solutions, specifically on the African continent, become a major disruptor?

In the not too distant future, we could see people across the African continent plugging in their electric vehicles to power their green homes. Combining solar energy with electric power from vehicles, houses could be completely off grid. Each house would produce its own energy which could be transferred across town by an electric vehicle.

Can you imagine the apps that could be dreamt up on the back of this scenario? This in turn will impact on how their cities plan for energy generation in the future – in the absence of the massive energy infrastructure presently powering developed cities across the world.

Cities in the developing world will be looking to the ‘new cities’ to see how to transform their existing centralised energy generation model to catch up with the developing world. Technology and innovation companies in the developing world will be playing a major role in these new futures.

There is a saying in Africa: "It is not the big that eat the small; it is the fast who eat the slow!" Should corporations and political leaders alike recreate the conditions of adversity to hasten innovation? Should businesses use this as a corporate strategy – i.e. ask its workforce in developing countries to find disruptors?

Perhaps we should be looking to the shanty towns for the next design innovators? If we apply this kind of innovation to developed economies, reverse innovation may just have the power to disrupt even our most innovative competition.

This blog was authored by: Abbas Jamie