Birds do it, bees do it, we all do it – produce tonnes of sewage each day that is. Our number ones and twos are not something we tend to wax lyrically about, but when we consider the alchemical wonder of digestion, we must admit it deserves a salutatory nod. The alimentary canal or digestive tract, has been described by one author as "the most important and least lovely waterway on earth." And yet it is indeed lovely, transforming food and drink into energy and life itself.

What about the labyrinth of sewers, the digestive system of our cities? A hundred years ago, we transformed unliveable cities into amazing places to live and improved societal well-being and prosperity. But, as we reach the limits of natural systems to assimilate our ever-increasing impact, with severe weather events on top of that, could we continue to describe our sewers as lovely and life-giving?

The very name associated with it, wastewater treatment, would suggest no. It's waste, refuse, decay. Something that takes inordinate amounts of energy, time and money to clean up in order to extract the one precious commodity from it – clean water.

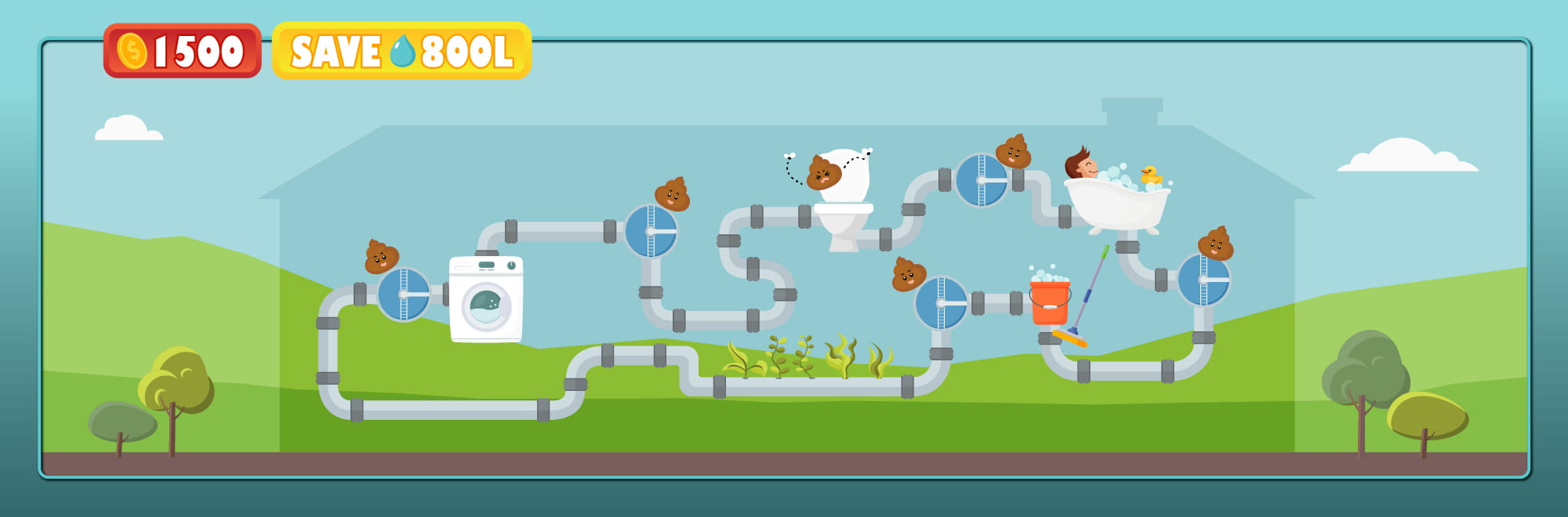

It raises a few questions: why do we still use pristine drinking water to transport our waste to giant cesspools? Why do we still treat our waste as a smelly problem when it is in fact a nutrient-dense, sustainable resource? Will we keep making our pipes and plants bigger and bigger? When will we account for the environmental externalities and how on earth are we going to change all this?

So much 'p-tential'

Ancient Rome knew the value of the daily bathroom deposit and collected so much human urine (prized for its ammonia content) that a urine tax was imposed on collectors. Money raised from this tax helped build the Colosseum. Londoners used to get a penny for their pail of liquid gold. Little did they know a century ago that if the 55-75 per cent of water in human faeces was extracted and the solid residue dried and concentrated, you would have a resource that has an energy content similar to that of coal.

At Brisbane's Luggage Point Sewage Treatment Plant is Urban Utilities' Innovation Centre, where you can make a urine deposit at the toilet amenities and have energy and nutrients extracted using UGold technology. It's estimated that globally, human waste converted to fuel could have a value of about $9.5 billion. Imagine if you got paid money for domestic sewage in the future instead of paying your quarterly utilities bill.

Humans produce about 290 billion kg of faeces per year and about 1.98 billion litres of urine. How's that for a sustainable resource? When in space, 290 litres of methane can be produced per crew per day, all produced in a week – enough to power their rocket back to earth. This is some pretty potent stuff. Paraphrasing Mark Watney in The Martian, "we're going to have to science the sh*t out of this stuff".

Combining both solid and liquid waste, a single human produces 4.5 kg of nitrogen per year, according to the World Health Organization. The urine one person produces annually contains enough fertiliser to grow nearly a whole year's supply of food. If you consider that a shortage of nitrogen fertiliser, due to soaring natural gas prices, is threatening to reduce global crop yields, flushing all those valuable nutrients down the drain proves to be the real waste.

And it looks like history is about to repeat itself…. it's about time. But we're not talking about putting a pail out each morning, technology has come a long way over the past hundred years, we have the resources to do it and the 'burning platform' for change.

The cycles of life

Just as it's become commonplace for houses across neighbourhoods to have solar panels on roofs, so too dwellings can have their own small household treatment plant responsible for turning sewer water into drinking water using the surplus energy from the roof.

Imagine households with a dishwasher-sized water treatment appliance installed in the bathroom or basement, which can process all human waste and wastewater for the day by flicking a switch or pressing a button. In addition, from this technology, you can produce water for any outdoor use or even a little bag of fertiliser for your veggie garden. While the technology has been around for a while, recent advancements are bringing it closer to mainstream installation than ever before.

In New Zealand, struvite ‒ a sewage treatment plant mineral phosphate by-product ‒ sells for over a $1000 a tonne wholesale or $4 a kilo at the local nursery. This started off as farm fertiliser on crops which goes through the food chain, through us and ends back as fertiliser ‒ the nutrient cycle exemplified.

In Namibia, one of the driest countries in Africa, they have been running a 'drinking water recovery from wastewater' system for over fifty years, making it the oldest Direct Potable Reuse (DPR) plant in the world. The city of Windhoek began to recycle wastewater for human consumption in 1968 and has been described as the cradle of water reclamation, people from all over the world visiting it to glean some insight into the art of water renewal.

Operation Next is an initiative working towards providing 70 per cent of drinking water for Los Angeles with Direct Potable Reuse by 2035.

Since 2015, San Francisco has made on-site water reuse systems mandatory for all new construction of more than 250 000 square feet of gross floor area. In line with this, one start-up developed a decentralised system that converts black and grey water on-site into recycled water for non-potable uses as well as beautiful, nutrient-rich compost. It is estimated that the system can help a building reduce its annual water demand by up to 95 per cent.

On a smaller scale, the Hydraloop is a stylish home appliance the size of a refrigerator which recycles up to 95 per cent of the household's grey water for non-potable usage. Research and development enterprise Blackwater Treatment Systems (BTS) is in the process of developing a micro treatment system that aims to convert domestic sewage into on-site reusable water.

How big an impact can we make on the driest inhabited continent if we fuse renewable energy and water treatment technologies to help build truly a circular economy?

Black, the new green

Many cities continue to rely on water and sewer infrastructure that is a hundred years old. Extremely costly upgrades or complete overhauling will soon be necessary. The timing is right to look at different solutions in many of our major cities. Will we come to a point where we do away with sewers altogether, or don’t need to enlarge the systems anymore?

England, like most countries, is facing a crisis of raw sewage flowing into rivers in storm overflows. Something that happened more than 200 000 times in 2019 and increases 37 per cent year-on-year. Suggestions ranging from sustainable drainage, use of artificial intelligence and doing away with sewers altogether are on the table. Every time a city floods, sewer overflows and bypasses contaminate the flood water and increase exposure to health hazards.

Our cities need to have a healthy and properly functioning digestive system if we are to thrive and, in a world subjected to climate change and rapid population growth, wastewater shouldn't be water wasted.

Wastewater utilities have to transition to the 'toilet as a service' concept and give customers choice or autonomy to operate as self-sufficient and self-sustainable water treatment entities. This is good for the household budget, great for the environment and will strengthen the national resilience. We won't be able to refuse reusing refuse for much longer.

This blog was co-authored by: Darren Romain