Can you safely stop by going faster? Or achieve a safer outcome by taking more risks? These apparently irreconcilable paradoxes make more sense if viewed within the context of a counterintuitive way of thinking.

Don’t scratch that itch. Sharp knives are safer than blunt knives. If you’re in a sinking vehicle, you should wait until water fills it before opening an exit. What do all these things have in common? They’re examples of counterintuitive thinking.

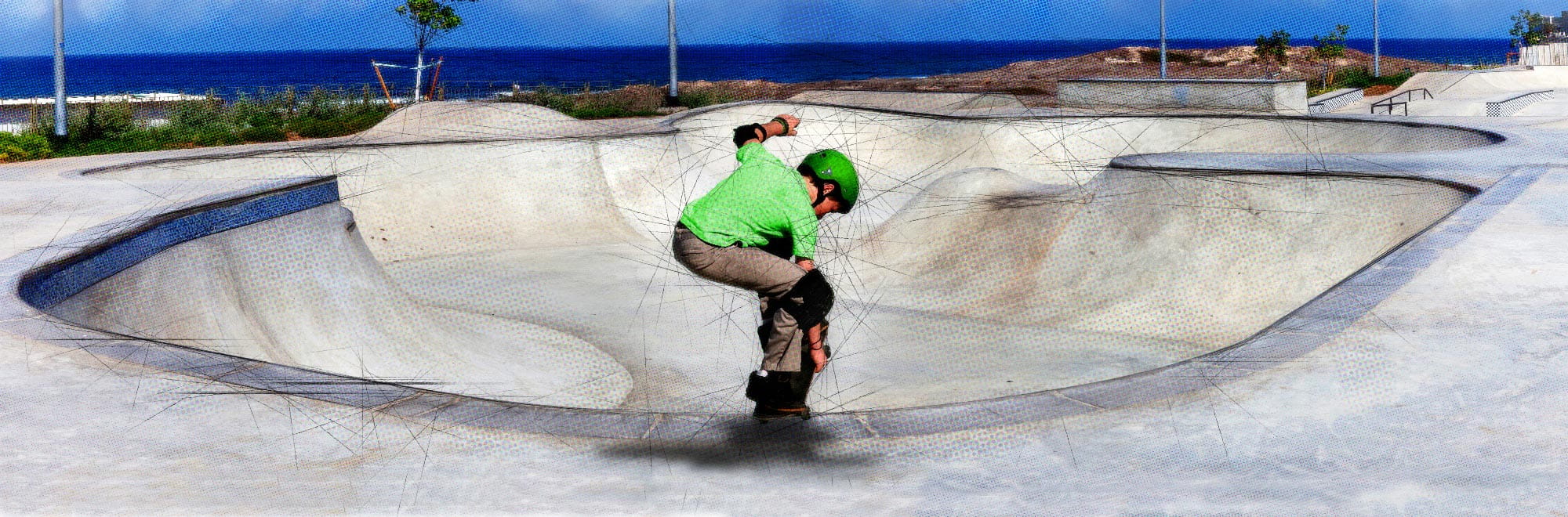

Counter intuitiveness is defined as being contrary to intuition or common-sense expectation. For example, some might think it’s counterintuitive (or crazy) to stand on the ledge of a concrete cliff like a skate ramp and launch oneself off, yet it is now an Olympic sport to do so.

In business, there are often processes and formulas to follow when trying to solve problems or develop new offerings. But what if we opened our minds and explored ways that difference can bring benefit? Counterintuitive thinking offers myriad ways of juxtaposing our approach to problem solving.

Going fast for a safer stop

Landing a commercial airliner on land is fairly intuitive: reverse thrust is applied and the pilot brakes hard; however, landing a plane on an aircraft carrier at sea is a different story. This scenario involves four parallel arresting wires and carrier planes are fitted with arresting hooks which snag the wire and this brings the plane to an abrupt stop.

However, as soon as the plane hits the deck, the pilot will push the plane’s engines to full power, instead of reducing thrust to slow down. It’s counterintuitive but if the tailhook doesn't catch any of the arresting wires, the plane needs to be moving quickly enough to take off again and come around for another pass. To not have full thrust deployed risks crashing into the sea.

Take more risks to increase safety

On a wet track, the secret to winning is to actually go faster and reduce the risk of crashing which is completely counterintuitive. The mind tells drivers to slow down but confidence in the wet comes from greater feedback and mechanical grip or feel. The harder competitors push, the more feedback they receive which leads to greater stability, precision through corners and earlier acceleration. Of course, competitors can still crash but overall, by going faster in the wet, it’s safer.

A similar ‘more haste, less waste’ concept applies to minimum viable product (MVP), a development technique that involves quickly moving a new product to market with basic features so the idea can be tested with consumers before refinement.

Famous examples include Dropbox, Airbnb and Foursquare. The concept of MVP is often credited with successful product development given it reduces the length of time spent on product development cycles and confirms whether a business model is viable early on.

Necessity to retrain the brain

Almost everyone uses their dominant hand when it comes to using a computer mouse. Like most everyone, I did this too but now I don’t. I’m not a genius nor multi-dexterous. I was forced to change because I injured my right elbow years ago. I couldn’t use a mouse right-handed while my elbow repaired for nearly 12 months.

At first, the change was agonising. It felt terrible, I had terrible fine motor skills in my left hand, was slow clicking and dragging and took time to adapt to using a right-hand mouse left-handed. But I had to persist, there was no alternative.

After a time, my skills and confidence increased, the weird became the norm. Today, I use a mouse left-handed by choice. And it has some benefits, I can actually take care of my on-screen mouse work and if I need to, make notes using my dominant right hand which I use to write. A counterintuitive action delivered a benefit for me.

Counterintuition and creativity

Counterintuitive thinking is rooted in our evolution and culture. It informs our appreciation of art, design, and architecture. As humans, we bend reality as we immerse ourselves in the ‘un-conventions’ of modern design. We marvel at a cantilever-levered design as it hovers above the ground, seemingly defying gravity.

Engineering keeps loads suspended but our search for creative expression and counterintuitive thinking drives these design concepts and their execution. Through these designs, reality is redefined and we are tricked into believing a building is floating or unsupported. At the core of these things:

Creativity was born out of counterintuitive thinking. It’s a way of thinking that inspires us to be different, see challenges differently and explore ourselves more deeply.

Age of the counterintuitive

As a result of the pandemic, the old world is…well, old. Even as our world is opening back up again, people don’t want to go back to the way things were or pick up where we left off.

After the two World Wars, everything changed because everything had changed. The roaring 20s, the great depression, after WWII, affluence rose in the 1950s, birth rates soared, freedoms were won, and the world was different. Out of upheaval and tragedy came a new way of thinking and living.

Counterintuitive thinking, accepting it or being comfortable with it, is just a different way of making decisions that can change our lives and those of people around us. It helps us consider situations and then explore how we might make sense of them in a different context.

This is useful when we accept that life is full of risks and when facing risks, there are a number of alternative responses we can take. We can focus on staving off the risks or become more resilient. If we only focus on managing risks, that is, believing that bad things might happen so we should be more cautious, we will slow our growth and might actually increase the risks we fear. We truncate learning and exploration – which is the enemy of diverse thought.

As then, we don’t know what we don’t know but we have the opportunity to embrace counterintuitive thinking to address things when they become known. Perhaps we might even get to become comfortable speeding up in order to safely slow down?

This blog was authored by: John Hardcastle