David Robinson, author of 'The Intelligence Trap', postulates a perplexing question that inflicts many a business or political party: "why do seemingly smart people do dumb things?" According to his research, doing dumb things and making dumb decisions are often more prevalent the smarter you get. It is supported by the cognitive bias of 'functional fixedness', which describes our tendency to see things only in one dimension, and doggedly stick to a particular viewpoint despite more logical options and explanations.

If there's anything we've learned in 2020, it's this: nothing remains permanent. Everything that we've known to be true, normal, or effective can change in a blink of an eye; and getting stuck to the idea of 'what has always worked' can lead us to failure or worse, an organisation's demise.

Goal-setting theories, such as those published by Dr Edwin Locke in 1960, have brought organisations and professionals a long way. Most narratives for building a high performing team espouse the benefit of having shared goals and sticking to them.

In fact, setting clear, written goals and plans to accomplish them were given as the reason why 3 per cent of Harvard MBA students make ten times more money than the other 97 per cent combined.

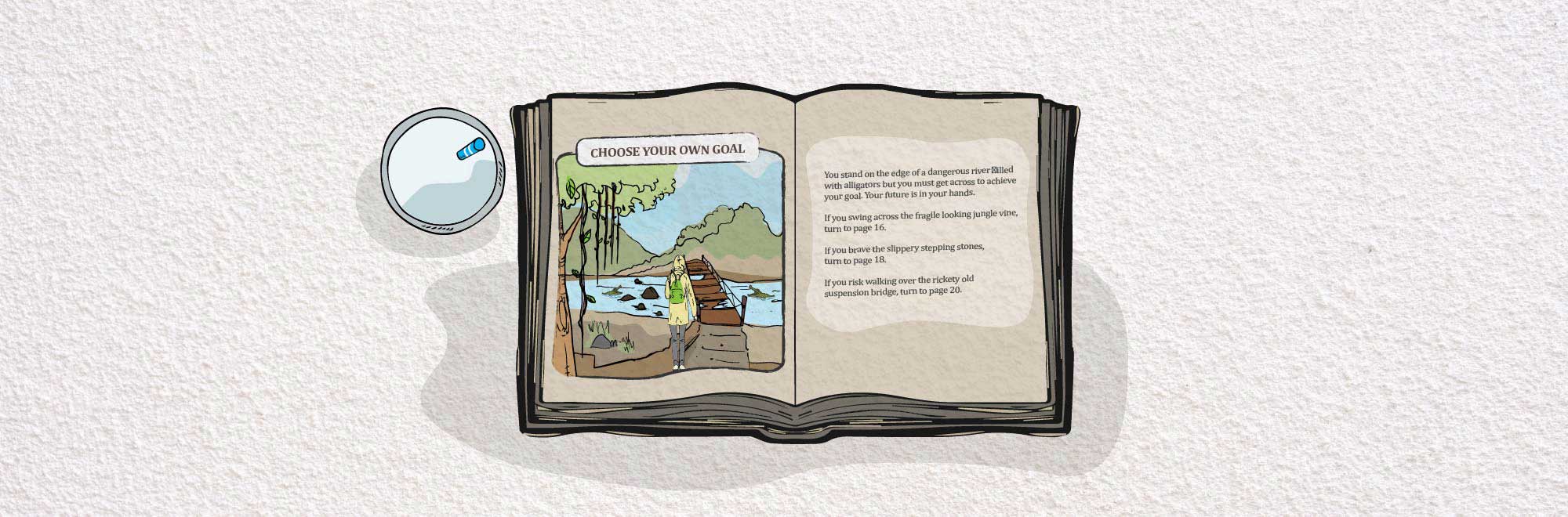

But is the traditional goal-setting still the smart way to success in today's world? Or, are SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Timebound) goals starting to become dumb?

The compass is broken

Focus, achievement and motivation are all great, but like Jekyll and Hyde, even the good can cast a less-than-wholesome shadow. While goals give us targets and guide our actions for achievement, there is also a high risk that they can set us on a path of directional myopia, of not seeing the wood for the trees and narrowing our thinking to other possibilities.

This and other negative consequences of goal-setting including a rise in unethical behaviour increased risk-taking, corrosion of organisational culture and reduced intrinsic motivation have been pointed out before, but now is the time to challenge this. You have to wonder what type of performance setting an organisation will need in a volatile economic world, when tomorrow's performance results are about as predictable as the weather.

Does the traditional practice of goal-based KPIs actually fuel the wrong behaviours that will be needed to navigate volatility from a disrupted world due to a pandemic? Is our fixedness on our goals making us counterproductive and impacting our performance in the long run? If we've failed fast and often too many times already, perhaps it's not just the actual goals that might be setting us off in the wrong direction, it's the belief system in goal-setting that we've built through the years.

Goal-setting has gone wild in terms of its impact on unmeasured outcomes and can even be outright dangerous. A classic example is the badly designed Ford Pinto, which claimed the lives of fifty-three people in the aim to build a car "that weighed under 2000 pounds and cost under $2000" in 1970.

Coca-Cola, also, has had its share of targeting the wrong goals after trying to reformulate their signature drink to make it more competitive with rival Pepsi without checking if their customers wanted it to change.

Ditch the numbers

Accomplishment is synonymous with success. But what if the fear of failure prevents you from reaching any achievement or even making an attempt to reach it? Believing you're failing, up until the point you reach your goal, will only plunder you from the inspiration and energy needed for the journey.

"When you set out these numbers and these goalposts and these goals and these expectations and you don't hit them, then you're upset. And once you've actually either hit them or not hit them, then you come up with another set. You just keep moving these moments of possible joy, but most likely disappointment in a lot of cases," says Basecamp CEO Jason Fried on The Tim Ferris podcast.

In fact, according to research, SMART goals don't always predict success as only 15 per cent of employees agreed that their goals will help them achieve great things, and only 13 per cent said their goals will help them maximise their potential.

Perhaps the better question to ask ourselves when setting up goals and metrics is: "Is there a problem to fix or area we need to improve on to begin with?" and "Why do we want to achieve these in the first place?" Numbers and statistics are meaningless without a profound purpose. Employees are likely to love their jobs and feel motivated to accomplish them if they set HARD (Heartfelt, Animated, Required and Difficult) goals instead of SMART ones, because they have far more emotional connections to these aspirations.

Clemson University psychologist Cynthia Pury explains that people tend to be braver in achieving their goals when they care about them. "Courage happens when someone perceives a valuable, meaningful goal in their environment. But to reach that goal, they have to take a personal risk, and they make a voluntary choice to do so," she said.

Keep your eyes on the system, not the goals

Ultimately, the function and dysfunction of goal-setting relies on how we perceive success. In James Clear's NY Times bestselling book Atomic Habits, he said the problem with goal setting is a "serious case of survivorship bias." We only tend to look at the winners (the survivors), and overlook those who didn't succeed even if they had the same objectives.

The intense fear of failure can be so overwhelming that it may cause us to either be paralysed to move forward, or be pushed to do everything to make it work, even if it makes them unethical. Either way, we lose. However, if we see a goal as a function of learning and growth, completely different behaviours are achieved.

We need to focus on establishing the process that delivers the goal, more than the goal itself. Process-oriented people attain goals because their process takes them in that direction naturally. They treat the journey as an end in itself: learning, growing, and mastering. Focusing on the process forces you to be in the moment: a powerful state of mind which can help you reach goals faster with much less fear and anxiety.

Whether or not our goals are attained, we are able to move forward evaluating and assessing what went wrong and how we can improve in the future. It allows us to celebrate our wins, whether they are big or small; and helps us to find the next path to take. There are no dead ends.

Our goals are tied to the future and must therefore be malleable – your future self could be vastly different from (or completely indifferent to) your present self. You need to be flexible if you want to stretch yourself. And perhaps success, as well as failure, should be redefined as continuous growth and progress – and not fixed.

This blog was authored by: Joyce Hipolito and Gillian Jarvis